Changing False Narratives in Public Health

Changing False Narratives in Public Health

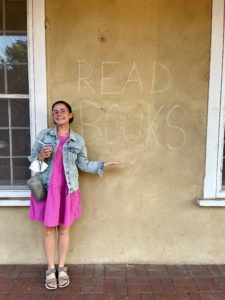

Nellie Kassebaum can’t stop thinking about the systemic nature of social issues.

If a person doesn’t have access to affordable housing, she reasons, then they probably don’t have a place to put food. Or an internet connection to apply for jobs. Or health insurance to pay for their high blood pressure medicine. Or the mental space to even think about how to improve these conditions.

As someone diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age nine, Kassebaum is particularly interested in the systemic nature of problems in America’s healthcare system. Moreover, she says, “The diagnosis made me realize that I needed a good job as an adult to get health insurance to pay for my insulin.”

Fortunately for the Center for Practical Bioethics, while completing her Master of Public Health degree with a focus in health communication at the Colorado School of Public Health, Kassebaum cold called Dr. Erika Blacksher to learn more about her work in population health and ended up being hired as research coordinator for the Center’s Civic Population Health Project.

Civic Population Health Project

The project is laying the groundwork for engagement and action through democratic deliberation, a process that brings people together from all walks of life, providing them with non-partisan educational materials, and creating a forum that enables them to learn about and discuss issues respectfully and find common ground.

In the initial phase of this multi-year undertaking, Blacksher and her team of experts are creating a toolkit that will provide a model, along with resource materials and metrics, for a pilot project in Kansas and Missouri.

“I am most excited about the project’s local and regional focus,” said Kassebaum. “This matters to me because rural public health ethics are often overlooked.”

Nellie keeps the project’s research team and expert advisory committee humming by scheduling calls, locating resources, doing background research, and developing the organizational structure for the toolkit and some of its elements.

“Nellie is a joy to work with,” said Blacksher. “She loves to learn and has a can-do attitude. On top of all that, she grew up in rural Kansas and knows it well. That experience and knowledge is very important as we move forward locating partners and test driving the democratic deliberative toolkit.”

Stop Blaming the Individual

Kassebaum was born and raised in Burdick, Kansas, about an hour south of Manhattan, on her parents’ cow-calf ranch.

“I spent a lot of time outdoors with my sister,” she said. “We had family dinner every night with discussions of current events and a dictionary and atlas close by.”

After graduating from the University of Kansas with a B.A. in English and minor in Public Policy, she spent a year in AmeriCorps’ City Year program working with third graders in Kansas City, Missouri.

“As a 22-year old, that experience instilled in me the necessity for human connection and for being vulnerable and just listening when you can’t really do anything else.”

It also crystalized her desire to change false narratives that frequently involve blaming the victim. Just as her Type 1 diabetes diagnosis had nothing to do with lifestyle choices, something all types of diabetics are often wrongly accused of, her City Year students’ learning challenges had nothing to do with intelligence or willingness to work hard and a lot to do with conditions beyond their control outside of school.

“I believe misplaced blame is the biggest issue in public health,” she said. “If the source of bad outcomes is not properly placed or understood, then the reaction can’t be appropriate.”

Kassebaum, who lives in Lawrence, Kansas, with her partner Austin, would like her career to continue on a path that elevates public health as an agent of change for building communities. And when time permits, her favorite challenge is cooking – particularly a steak or a pot roast – for friends and family.